How much should you actually save for retirement? Everyone from your brother-in-law to your favorite (or least favorite) financial pundit has a view. But, are those opinions even remotely accurate?

As opposed to pontificating about retirement rules of thumb, let’s use financial planning software and look at an example.

Before we dive in, note that the following items are presented for educational purposes only. Nothing here is or should be considered specific financial advice for you. As your situation is undoubtedly nuanced, you should seek the advice of financial and tax professionals before utilizing the strategies mentioned.

How Much Do “Jessica and Tom” Need to Save?

To avoid turning turn a few hundred words into several thousand, we’ll concentrate on retirement planning for a simulated couple: Jessica and Tom*. We’ll exclude saving for college, caring for aging parents, and countless other situations and complicators.

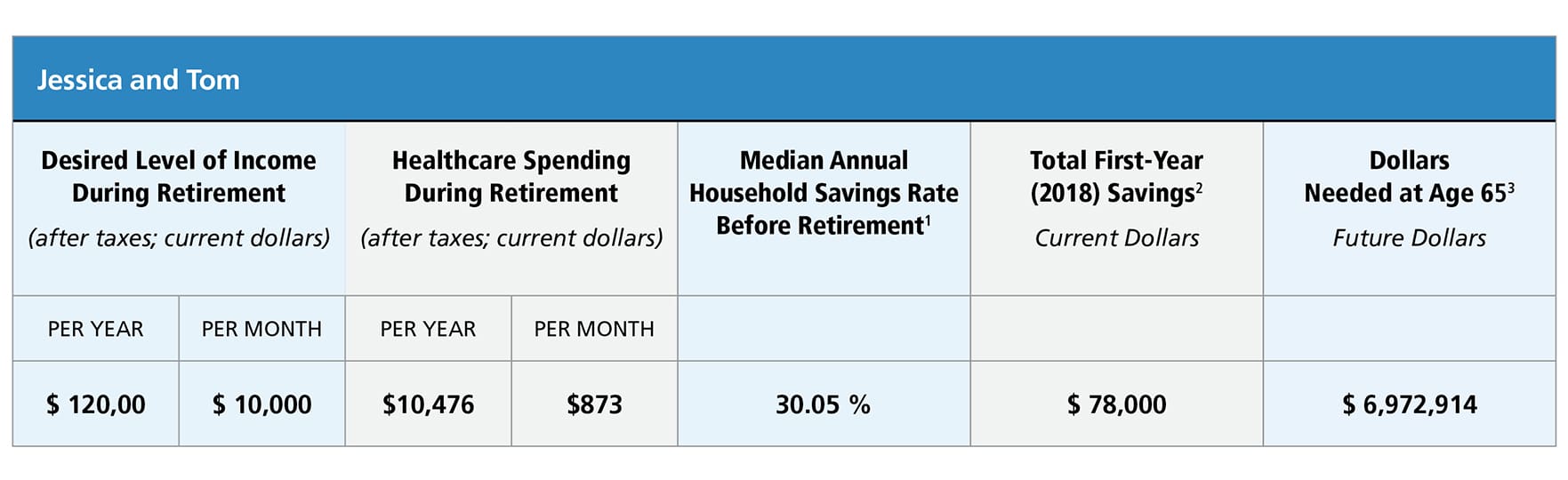

Both 40, Jessica and Tom want to retire, or at least have the freedom to stop working fulltime at 65. Jessica is an in-house attorney at a medium-sized manufacturer and Tom works in healthcare administration at a local hospital. Together they make $300,000 before taxes and have saved $250,000 between their 401(k)s. Since Jessica and Tom are 40, they have 25 years until they retire at 65. They both expect to live until age 95, so they need their savings to last for 30 years.

We start by determining how much Jessica and Tom need per month to maintain their current standard of living throughout retirement. This is accomplished by analyzing their spending, removing items that’ll go away before retirement (kid-related expenses and hopefully, their mortgage), and by adding items that will likely be present during retirement (healthcare expenses).

Let’s say we’ve arrived at $10,000 per month for regular living expenses and $873 per month for healthcare expenses. Both figures are in current after-tax dollars. Regular living expenses and healthcare expenses are separated as they tend to inflate at different rates: In these projections, regular living at increases 3 percent per year and healthcare at 5 percent per year.

What Does All This Mean?

Based on myriad assumptions (scroll down to see them), Jessica and Tom will need to have saved approximately $6.9 million (in future, inflated dollars) when they retire at age 65. (That’s $3.7 million in today’s dollars.) This plan has an 86 percent probability of success of being able to provide Jessica and Tom with an inflation-adjusted $10,000 per month for regular living expenses and $873 per month for healthcare expenses, starting at age 65, and continuing throughout their retirement (30 years).

“Total First Year (2018) Savings” includes:

- Jessica and Tom’s 401(k) contributions: They’re both maxing out their accounts; $18,500 multiplied by 2 equals $37,000 per year.

- Their employers’ matching contribution: 3 percent for both Jessica and Tom equals $9,000 per year.

- Contributions to a taxable investment account of $32,000 per year.

- $37,000 plus $9,000 plus $32,000 equals $78,000 per year, total.

Jessica and Tom’s 401(k) savings are assumed to rise as IRS contribution maximums are increased annually. While their employers’ match percentage remains at 3 percent, Jessica and Tom’s salaries inflate at 2.56 percent per year, so each year, the actual dollar amount of their employers’ contributions should rise.

Where did 86 percent come from? Incorporating our assumptions, the financial planning software ran a Monte Carlo analysis simulating 1,000 different trials of varying market returns. Out of those 1,000 trials, Jessica and Tom’s plan succeeded 86 percent of the time.

A key assumption is that no additional changes were made to any of the inputs up to and throughout retirement. This is somewhat unrealistic. If your plan appeared to be failing — let’s say you didn’t save enough and inflation crept up higher than expected — you wouldn’t sit idly, knowingly draining your assets prematurely. You’d adjust your spending, look for contract work, or do something to correct your plan.

If 86 percent is a “B” … I want an “A.” Don’t we all. Planners generally view probabilities of success in the mid-to-high 80s as ideal. Once these scores edge into the 90s, you may be sacrificing some of your current lifestyle via over-saving (yes, there is such a thing).

Why not 100 percent? This would imply some level of guarantee. No plan is bulletproof; even the best analysis methods have their drawbacks.

How Much to Save for Retirement? What’s Important, Three Things

Control the controllable. You manage (or at least influence):

- Desired monthly spending

- Savings rate and/or

- Retirement date

These are the three most powerful drivers of your retirement’s success or failure. Drop your required spending, boost your savings, or push back your retirement date (or do all three) and your probability of success will rise. Small changes make a huge difference.

What’s Less Important

Rate of return. Why couldn’t Jessica and Tom have exposed their investments to a larger percentage of risky or growth-oriented assets (think: stocks) and have benefited, in theory, from a higher rate of return, thus decreasing their needed savings?

If only markets would cooperate with your retirement timeline. If your financial plan only works with a consistent elevated rate of return, you need to reassess things immediately. Markets have a tendency of not cooperating when you need it the most. Do not rely on them to bail you out.

Future money. When only future raises, bonuses and windfalls will make your financial plan work, trouble is on the horizon. If you’re having difficulty saving enough on a $300,000 per year income, then $350,000 or $400,000 per year likely won’t fix the situation. Money habits, both good and bad, tend to expand with your income.

Terms Defined

1. Median annual household savings rate before retirement. The following formula was used:

Annual savings rate = [ (Jessica and Tom’s annual savings) +

(employers’ contributions) ] ÷ (Jessica and Tom’s combined pretax income)

The median value was calculated from the 25 annual savings rates. Household savings includes contributions from your employer.

2. Total first year (2018) savings. The amount that Jessica and Tom will save, plus the amount their employer will contribute in 2018. This amount changes each year as their salaries are projected to increase and retirement plan contribution limits are projected to increase.

3. Dollars needed at age 65 (future dollars). For each level of desired spending, Jessica and Tom would need to have saved the corresponding amount of money by their retirement at age 65. These amounts are in future, inflated dollars.

How Much to Save for Retirement: Major Assumptions

- Current age of Jessica and Tom: 40 (for both).

- Target retirement age: 65 (for both).

- Plan end date: 95 (for both).

- Inflation for general expenses: 3.00 percent per year.

- General expense target in retirement: $10,000 per month (current dollars; after tax).

- Inflation for healthcare expenses: 5.00 percent per year.

- Healthcare expense target in retirement: $873 per month (current dollars; after tax)

- Inflation of salaries: 2.56 percent per year.

- Starting assets at age 40 in 2018: Jessica’s 401(k): $125,000 (all pretax); Tom’s 401(k): $125,000 (all pretax).

- Rate of return on investments before retirement: 6.00 percent per year.

- Rate of return on investments during retirement: 4.00 percent per year.

- Advisory and transaction fees: none.

- Taxes: estimated by financial planning software.

- Social Security Income was estimated based on Jessica and Tom’s gross/pretax salaries, $150,000 per year for each. For conservatism, these Social Security Income estimates were reduced by 20 percent.

- Jessica and Tom claim Social Security at age 67. For conservatism, their Social Security Income estimates were reduced by 20 percent.

- Inheritance: none.

- Business sale: none.

- Pension: none.

- Insurance: long-term care and life insurance sensitivities were not incorporated.

- Retirement plan contributions: see scenarios above.

- Monte Carlo analysis runs 1,000 trials or varying market retunes and volatility to produce a probability of success of a financial plan without making any changes or adjustments along the way.

- Financial planning software: eMoney / eMoney Advisor, LLC. (Software Version: 10.3.284.501).

- Planning projections should be revisited at least annually.

*The couple described in the examples above was created for this post. Any similarities to persons, alive or dead, are purely coincidental. As with all financial and investment projections and forecasts, past performance and experience are not indicative of future results. Future results may be lower or “worse than” past results. Nothing described is guaranteed in any capacity.

Illustration ©iStockPhoto.com

Subscribe to Attorney at Work

Get really good ideas every day: Subscribe to the Daily Dispatch and Weekly Wrap (it’s free). Follow us on Twitter @attnyatwork.