In his latest book, Richard Susskind’s goal isn’t to sell hype or pour cold water on everything — it’s to replace fuzzy impressions with crisp mental models. Make sense of AI’s impact on the legal profession. Our review explains how Susskind’s book provides clarity for perplexed lawyers.

Table of contents

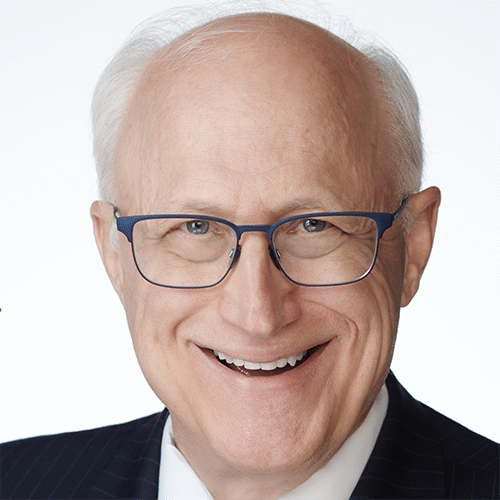

Richard Susskind is what I call a Big Thinker — the kind of legal technology sage who delivers keynote speeches by the dozen and publishes deep thoughts in serious journals. He has a rare talent for synthesizing complex ideas and explaining them in a clear and engaging way. For lawyers and policymakers trying to make sense of AI’s impact, ”How to Think About AI: A Guide for the Perplexed” may be Susskind’s most timely and clarifying work yet.

“How to Think About AI: A Guide for the Perplexed” by Richard Susskind. Oxford University Press, 2025. 224 pages. A short, non-technical guide that challenges us to think differently about AI.

Available from Bookshop.org (supports independent booksellers), Barnes & Noble and Amazon.

Replacing Fuzzy Thinking with Clear Models

This is not a book of answers. It is a book of questions. Susskind does not pretend to have solutions to all thorny issues around artificial intelligence. His goal is to help readers identify the issues and suggest some clear ways of thinking about them. Susskind’s goal isn’t to sell hype or pour cold water on everything; it’s to replace fuzzy impressions with crisp mental models.

Readers tired of AI discourse that either cheerleads everything or condemns it wholesale will likely find the author’s thoughtful and balanced approach refreshing.

Susskind makes complex ideas accessible to both lay readers and specialists. The book does double duty as a confidence booster for laypeople and a reality check for insiders who may be over- or under-reacting to recent breakthroughs. Cramming all this into 224 pages is quite a feat.

Key Concepts in How to Think About AI

Chapter 1, “The Summer of AI,” is a brisk summary of AI’s past, present, and plausible futures. Susskind sketches the early dreams of computer scientists, the winters when funding dried up, the deep-learning renaissance of the 2010s, and the current era of generative models. From there he invites readers to imagine where things might go next: self-improving systems, autonomous researchers, or tools that seamlessly blend into everyday life. This history lesson isn’t just trivia. It’s used to show repeating patterns — overpromising, backlash, steady progress — that help us spot what’s truly new this time.

Chapter 2, “On Technology,” contains a warning:

We’re still warming up. In not many years, our current technologies will look primitive, much as our 1980s kit appears antiquated today. [The current wave of AI apps] are our faltering first infant steps. Most predictions about the future are in my view irredeemably flawed because they ignore the not yet invented technologies.

He notes that Ray Kurzweil’s “law of accelerating returns” appears to be coming into play: “Information technologies like computing get exponentially cheaper because each advance makes it easier to design the next stage of their own evolution.”

These are probably the reasons why even top computer scientists, including Stephen Wolfram, cannot explain how generative AI works. Susskind quotes Wolfram: “It’s complicated in there, and we don’t understand it — even though in the end it’s producing recognizable human language.”

The implication? We’re not just on a new road — we may be building a new kind of vehicle while already driving at speed.

The “process vs. outcome” distinction.

Chapter 3, “Process-thinking and Outcome-thinking,” sets the stage for following chapters by contrasting the views of two heavyweight public intellectuals: Henry Kissinger and Noam Chomsky. Kissinger praises AI to the heavens. Chomsky thinks it’s basically worthless. Susskind’s explanation for the contrasts is that Kissinger focuses on outputs, while Chomsky focuses on process:

- Process-thinkers are interested in how complex systems work.

- Outcome-thinkers are interested in the results they bring.

- Process-thinkers are interested in the architecture of systems.

- Outcome-thinkers concentrate on their function.

- Outcome-thinkers also tend to be “bottom-up” thinkers, preoccupied with overall impact.

This is a key distinction that explains a lot about differences of opinion about AI. Since AI apps don’t think the way humans think, process-thinkers tend to dismiss them as useless. Outcome-thinkers are more pragmatic, focusing on the demonstrable practical benefits. They understand that “machines don’t need to copy us to deliver the outcomes or outputs that customers, clients and users want from their providers.” Lawyers, trained to analyze process, may be predisposed to dismiss AI’s unfamiliar logic, missing the forest (useful results) for the trees (alien methods).

Diving Further Into Concepts

Next up, Chapter 4, titled “Confusions,” explains some AI fallacies. This includes how process-thinking can contribute to myopia about AI and its effects, including “Not-Us” thinking:

Professionals see much greater scope for AI in disciplines other than their own. Doctors are quick to suggest that AI has great potential in law, accounting and architecture, but instinctively they tend to resist its deployment in health care. Lawyers assert confidently that audit, journalism and management consulting are ripe for displacement but offer special pleadings on its very limited suitability in the practice of law and the administration of justice.

Chapter 5, “We Don’t Have the Words,” makes the point that talking about AI requires a new vocabulary. For example, AI skeptics are fond of saying that computers can never replace them because they don’t have the same judgment, empathy and creativity.

What’s overlooked is that computers can provide what we might call quasi-judgment, quasi-empathy and quasi-creativity. Susskind demonstrates — quite convincingly — that the computer versions of these biological traits can be superior in several ways to the human version. Skeptical about this? All I can say is check out Chapter 5 before becoming too confident that you are irreplaceable.

In Chapters 6 and 7, Susskind considers how AI might change the workplace. This includes distinguishing three concepts:

- Automation (task substitution) is about finding a way to be more efficient about doing what we are doing now.

- Innovation means delivering the outcomes clients want, using techniques or technology that support radically new underlying processes.

- Elimination means not just solving a problem but eliminating it.

Many analysts see automation as the biggest AI threat to jobs. Innovation and elimination may be bigger dangers. Susskind makes a convincing case — to me, at any rate — that using AI to implement different approaches to conflict resolution or prevention of legal problems could reduce or replace litigation as we know it.

Sisskind’s seven categories of AI risk.

Chapters 8 and 9 deal with AI risks and how to address them. Rather than engage in unfocused handwringing about the risks of AI, Susskind organizes his analysis using a simple table:

| CATEGORIES OF AI RISK | |

| Category 1: Existential Risks | Threats to the long-term survival or potential of humanity. |

| Category 2: Risks of Catastrophe | Large-scale disasters or societal disruptions short of extinction. |

| Category 3: Political Risks | Impacts on democracy, governance, surveillance, and autonomy. |

| Category 4: Socio-Economic Risks | Effects on employment, inequality, social cohesion, and bias. |

| Category 5: Risks of Unreliability | Issues arising from AI errors, inaccuracies, or “hallucinations.” |

| Category 6: Risks of Reliance | Dangers of over-dependence or inappropriate trust in AI systems. |

| Category 7: Risks of Inaction | Negative consequences of failing to develop or deploy beneficial AI. |

Having laid out the risks, Susskind provides suggestions for dealing with them. He emphasizes measured urgency rather than end-of-the-world hysteria. His message is that policymakers and the public need to grasp the size and speed of current AI shifts, not because disaster is inevitable, but because decisions made in the next few years will ripple for decades. The subtext: Burying your head in the sand isn’t a neutral act — it quietly hands the steering wheel to whoever is paying attention.

The final three chapters address philosophical ideas and speculation as to what the future may hold for AI — and humanity. Discussions of Plato’s allegory of the cave, umwelten and Kant’s distinctions between phenomena and noumena most likely won’t engage the attention of every lawyer, but Susskind’s conclusion most likely will:

My guess is that we have at least a decade to decide what we want for humanity and then to act upon that decision — if necessary, emphatically and pre-emptively — through nation and international law. [O]ur future will depend largely on how we react over the next few years.

What Does All This Have to Do with Lawyers?

ABA Formal Opinion 512 translates abstract concerns about AI into concrete ethical obligations for lawyers, demanding competence in understanding AI’s benefits and risks (Model Rule 1.1), diligence in protecting client confidentiality (Model Rule 1.6), clarity in client communications (Model Rule 1.4), candor toward tribunals (Model Rule 3.3), effective supervision of AI use (Model Rules 5.1, 5.3), and reasonableness in fees (Model Rule 1.5).

While not an ethics compliance manual, Susskind’s book offers precisely the conceptual tools — the “mental models” — needed to navigate these practical obligations. For example:

- Susskind’s discussions on AI capabilities, limitations, and the difficulty in explaining how some systems work (Chapters 1, 2 and 5) directly inform the duty of competence under Rule 1.1, which requires lawyers to understand the benefits and risks of associated technology.

- His structured analysis of AI risks (Chapters 8 and 9) provides a framework for assessing potential threats to confidentiality under Rule 1.6, particularly concerning data security and inadvertent disclosure when using third-party AI tools.

- Exploring the “process vs. outcome” distinction (Chapter 3) can illuminate challenges in communicating AI use to clients (Rule 1.4) or ensuring candor to tribunals (Rule 3.3) about the origins and reliability of AI-generated materials.

The value proposition of Susskind’s book lies significantly in equipping lawyers with the cognitive framework necessary to operationalize the ethical requirements newly formalized in Opinion 512.

Don’t Get Left Behind: Read Susskind on AI

With over 500 generative AI apps for lawyers cataloged by LegalTech Hub in March 2025, the proliferation of such tools shows no signs of slowing. In this environment, nuanced understanding is more critical than simply another application. What the world needs is clear explanations of the ways AI is changing our world now — and what we can expect tomorrow.

Whether you’re writing briefs, litigating high-stakes matters, lobbying policymakers or just trying to future-proof a career, Susskind’s book aims to give you enough clarity to steer rather than drift. And in the AI era, that might be the most practical gift of all.

“How to Think About AI” is the literary equivalent of a well-lit observation deck overlooking a stormy sea. It is as much about society, ethics and identity as it is about neural networks. For attorneys plotting strategy in a generative-AI world, this book is required reading.

“How to Think About AI: A Guide for the Perplexed” by Richard Susskind. Oxford University Press, 2025. 224 pages. Available from Bookshop.org (supports independent booksellers), Barnes & Noble, and Amazon.

Image © iStockPhoto.com.

Sign up for Attorney at Work’s daily practice tips newsletter here and subscribe to our podcast, Attorney at Work Today.